Ambiguous Loss

Posted 30 September 2019, by Daria Belostotckaia

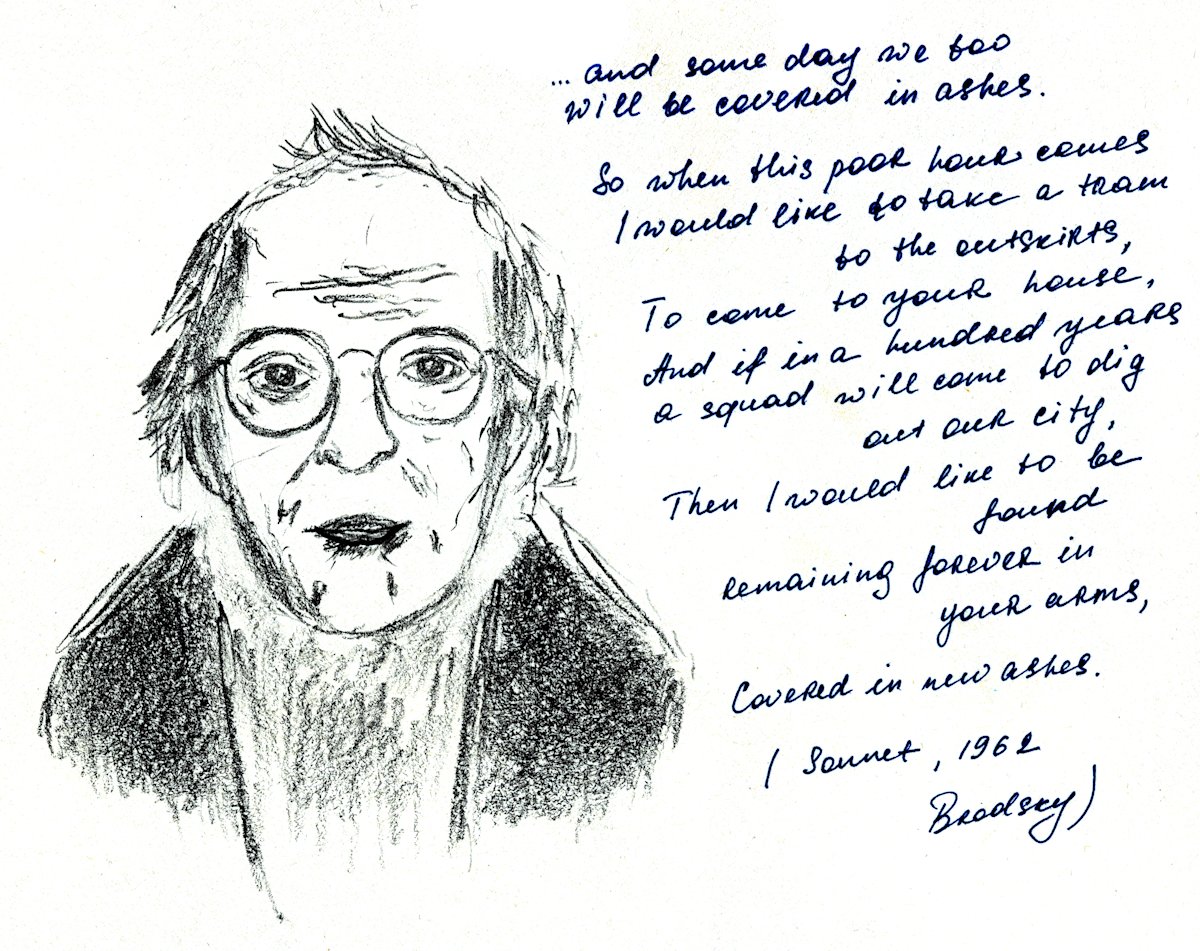

My favourite essay (and one I consider to be among the best ever written) is Joseph Brodsky’s In a Room and a Half. Brodsky describes how – after he was expelled from Russia – he and his parents were denied permission to visit each other for twelve years in a row, and even after they died, he wasn’t allowed into the country to be at their funerals. The essay is a collection of memories, pieces, fragments Brodsky remembered and wondered about his parents’ life, a reflection on the nagging, impenetrable pain caused by losing people to whom he was never able to say goodbye. Psychologists call this kind of loss ‘ambiguous loss’.

“Out of seventy-eight years of her life and eighty of his, I’ve spent only thirty-two years with them. I know almost nothing about how they met, about their courtship; I don’t even know in what year they were married. Nor do I know the way they lived the last eleven or twelve years of their lives, the years without me. Since I am never to learn it, I’d better assume that the routine was the usual, that perhaps they were even better off without me: in terms both of money and of not having to worry about my being rearrested.

<...>

I don’t and I never will know how they felt during those last years of their life. How many times they were scared, how many times they felt prepared to die, how they felt then, reprieved, how they would resume hoping that the three of us would get together again.”

The concept of ambiguous loss was developed by psychologist Pauline Boss, and can be of two kinds: one of psychological absence and physical presence, the other with physical absence and psychological presence. The former is the estranged partner, the child who has – so quickly – grown up and moved out of home. The latter is the missing person, or as in Brodsky’s case, the parents separated by an ocean and an iron curtain. The rituals we fill our life – and death – with are, in many ways, to keep us sane. We need to know what’s to come, we need to know what to believe in and how to cope. And when someone close dies, we need to see their body to reassure ourselves of this unique finality, and then we need to have a ceremony – some way to say goodbye, and to start the grieving process. A loss that lacks such rituals means that we will keep looking for people who ‘disappeared’, hoping that in some crazy way we made it up, we misheard, misunderstood, that there was a mistake. We won’t, for a very long time, be able to let go. Instead of going through loss, we will be living with it.

“No, it’s more likely that, now that they are dead, I see their life as it was then; and then their life included me.”

Another common trait of ambiguous loss is its subtlety. Because there is often no event, no place, no time of death, it comes as something that happened as if by the way, catching you somewhere between the supermarket and the post office.

“The thing was hearing each other’s voice, assuring ourselves in this animal way of our retrospective existences. It was mostly non-semantic, and small wonder that I remember no particulars except father’s reply on the third day of my mother’s being in the hospital. “How is Masya?” I asked. “Well, Masya is no more, you know,” he said. The “you know” was there because on this occasion, too, he tried to be euphemistic.”

Wars, terrorist attacks, and natural disasters all result in missing people, and loved ones without a body to bury. They are examples of unbearable, complex cases of ambiguous loss with physical absence and psychological presence. There are others, too.

Cases of ambiguous loss with people being physically there but psychologically inaccessible are much slower, even more subtle, harder to explain. They are also often more ordinary. Divorce, failed relationships, losing a person’s former self, to ageing, to growing up, to mental illness, to dementia. And then there is the loss within. Transitions we go through in ourselves – giving up on our past selves, going through mental illness, losing our identities, or just simply changing.

Having lived in several countries for the past five years, having only a vague sense of home, not knowing where to go, being on my own most of the time, I went through different stages. Those were crises of immigration. During which I had things – memories, music, books, habits – things that I’ve loved and was attached to all my life, as if they were lights that I could follow to come back to my old self at any time. But then – I don’t know when exactly – those things that I loved stopped serving the same purpose. They don’t lead me anywhere anymore (though they can still make me incredibly sad).

Last month I was listening to music that I’d listened to almost every day for more than 20 years, and the sadness I experienced was a lot like the one I’d have felt if I had just parted with my dearest friend. I don’t really know how to say goodbye to myself. Changing within the mix of cultures, languages, and people who surround you gets complicated. One becomes an outsider everywhere – too much of a foreigner abroad, too much of an expat back home – trying to protect the values of each group from the other, and to hold onto both. Some people are still there, old relationships are still alive. You can put on any music you want, read books in your mother tongue, come back to the country of your birth. But it’s not quite the same. And apart from experiencing these losses ourselves, we take other people on this journey. But for them, it’s often a completely different experience, their own loss. It’s very likely we won’t notice it and even if we do, we’re unable to help because the change has already started.

I don’t have an ending to this post, it’s hard to draw a line under something that is, by definition, ambiguous. I will say this though – admitting this kind of loss, in others and in ourselves, without the intention to get over it, is the right way to go. And with time, we process things. It took Brodsky more than a decade from the start of his exile to write In a Room and a Half. But given time, he dug out his life – and that of his parents – from under the ruins, building bridges between one continent and the other, between him and them, between life and death. He used language with the hope of finding freedom, human freedom to live, to grieve and to remember.

You can read more about ambiguous loss at Pauline Boss' website, watch her talk about it on Youtube, or listen to her talking to Krista Tippet on On Being.